In July 2025, the Government announced the launch of the new £500m Better Futures Fund. This will invest in social outcomes partnerships across the UK over the next decade to improve the lives of vulnerable children and young people. Being led by DCMS, this ambitious initiative is the largest social outcomes fund in the world and confirms the UK as a world leader in impact investment. It is hoped that the Fund will attract a further £500m of investment from local government, social investors and philanthropists.

At the same time, the Government have also formalised a new Civil Society Covenant which highlights the essential role that civil society, philanthropy and social investment play in our national life. It is clear that the role of impact investment in the UK is set to continue growing in the coming years.

Whilst there is much detail yet to sort out in getting the Better Futures Fund up and running, we already have a lot of experience in the UK in designing and delivering social outcomes partnerships. Resonance has been part of this learning process, having facilitated such partnerships itself.

To assist potential partners in preparing for the Better Futures Fund, this paper sets-out some important learning points. We are sharing this paper to contribute to the unfolding national conversation about how to make social outcomes partnerships deliver the greatest impact for the best value:

1.1 | Definition

Social Outcomes Contracts (SOCs) are contracts for the delivery of services to improve outcomes for people with complex needs, where some or all of the contractual payments are linked to the achievement of specified outcomes for a particular cohort of beneficiaries and where the contract relies at least partly on social investment. They are sometimes known as Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) or Social Outcomes Partnerships (SOPs).

SOCs have particular value in addressing complex social needs where innovation and flexibility in service design are required to personalise services and deliver better and faster outcomes than traditional siloed public services can achieve. There is often an element of early intervention too, reducing potential future costs for public services.

With payments predicated upon results (sometimes blended with part payments for activities) the contracts require working capital for the delivery partner, thus setting up a three-way relationship between commissioner, delivery partner and social investor (and sometimes adding others facilitating partners; investment intermediaries, technical advisors, etc). The social investor takes on the risks of non-delivery, but also shares in the rewards for successful delivery. Sometimes a Special Purpose Vehicle may be created, to manage the flows of funds in a project, but sometimes investment flows directly to the service provider.

1.2 | National overview

In the decade since the first Social Impact Bond launched, nearly 100 contracts have been agreed, making the UK a global leader, accounting for nearly one third of the world’s outcomes-based contracts [1]. In the UK, over 180 commissioners from across central and local government have worked with 220 delivery partners to benefit over 55,000 people.

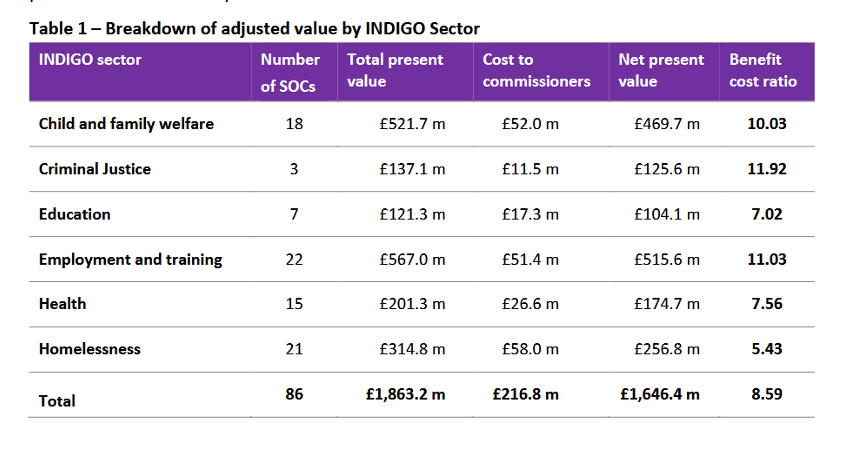

A comprehensive analysis of the SOCs market was undertaken in 2024 [2] for Better Society Capital (BSC). It analysed 86 SOC contracts from the last ten years and found that, up to 2023:

The number of SOCs being initiated since 2021 has stalled, suggesting that the ‘market’ is still largely driven by the availability of specialist Government funds [3]. The UK Government has so far launched ten Outcomes Funds since 2010, with a total value of £235m. The two most recent funds are the £80m Life Chances Fund (launched 2016) and the £14m Refugee Transitions Outcomes Fund (launched 2022) both of which are still operational.

Models have become more flexible and hybridised over the last ten years with some payments for activities, not just outcomes, and a slightly more relaxed approach to performance management. Growing experience and confidence does seem to be leading to more mature and manageable contracts, although it remains a small part of the social investment sector and a minority sport for most commissioners.

1.3 | Benefits of SOCs

The key benefits of SOCs which are highlighted in the published evidence include the following:

One example of how this feels on the ground is from a study of how a social impact bond felt like from the inside:

“We had a group of people that were experiencing …complex and multiple needs, not having access to development support services and actually we needed to do something different to … meet their needs and this project … enabled us to look at some of the problems across the system … it gave us an opportunity to draw everybody together to … try and put something in place to try and address this complex and wicked issue ... So that is a huge positive, without that we wouldn’t have had this [project].” (Frontline worker in a homeless charity, 2021)

1.4 | Challenges of SOCs

A number of challenges are also regularly highlighted in relation to the design and implementation of SOCs:

1.5 | Summary of lessons learnt from design and implementation

This is a summary of the practical ‘lessons learnt’ from a range of evaluations, highlighting issues for future SOC commissioners to be aware of. These focus on the ‘how’:

This section summarises the experience of Resonance’s involvement in investing in SOCs. Resonance has had direct involvement in SOCs addressing street homelessness as well as youth offending. Two partnerships are briefly described here, together with a summary of some of our learning.

2.1 | The Skill Mill Partnership: helping young people move away from re-offending

The Skill Mill is a social enterprise which works with young ex-offenders across a number of locations in England to support them to transition away from offending through training and employment, using real paid work experience, progress to recognised qualifications and support.

The Skill Mill were successful in securing support through the Life Chances Fund and a SOC was constructed by Social Finance. The design and delivery was initially complicated by Covid, and it took several iterations to finalise the approach, but overall, the finally agreed plan was to run a contract to:

The aim of the project was to scale up an existing and successful project – it was not seeking to innovate service design but to grow rapidly and beyond the North-East. The project was highly unusual for a SOC in that it relied quite significantly on earned revenue from trading (selling services to employers).

Resonance supported this project through a £100k unsecured loan from its West Midlands SITR Fund. Other social investment came through Big Issue Invest and North Star Ventures through unsecured loans and a small element of equity.

The project has been evaluated by Policy Evaluation & Research Unit of Manchester Metropolitan University as part of the wider Life Chances Fund Evaluation led by the Government Outcomes Lab. [13]

2.2 | Street Impact, Bristol: Transitioning from rough sleeping

The Entrenched Rough Sleepers project in Bristol was part of a nationally funded programme and was delivered on the ground by three organisations including St Mungo’s. It was commissioned for £1.25m by Bristol City Council to support 125 people out of rough sleeping.

The plan was to deliver an unsecured loan of £122.5k from the Resonance Bristol SITR Fund in 2017, as part of £273k investment into the SPV created for the project. The three charities also contributed £16k equity investments. The Resonance debt was subordinate to a CAF Venturesome loan.

2.3 | Learning points

From our experience of investing in SOCs in recent years, we have learned a great deal about the reality of how these partnerships operate. A summary of our learning includes these points, each of which is picked up and addressed in the final section of this paper:

This third part of the paper sets out a new and revised approach to designing and delivering SOCs in the UK, drawing on our review of the evidence base as well as our own experience of assisting in SOC delivery. We are putting forward new ideas for how the Better Futures Fund could be designed to deliver more effective partnerships.

3.1 | Potential not realised

Resonance’s own involvement with SOCs has shown us first-hand the enormous potential of this style of approach. SOCs, done well, can deliver joined up services and innovation which can transform lives – whether it is reducing the re-offending rates of young people or supporting homeless people to once again live independent lives in their own home. SOCs can deliver outcomes that are elusive to more conventional modes of delivery. They have an important contribution to make to public service delivery.

And yet.

It is quite clear after a decade of practice that the current approach is too complex, too costly and too challenging for too many public sector commissioners. When the national programmes of commissioner subsidies stop, so do the SOCs. The approach is not gaining momentum nor scaling up, simply waiting for the next subsidy, stuck in a frustrating cycle where the approach delivers good outcomes but never progresses to a stage of scaling up. We think this is a missed opportunity.

It is our contention that until significant changes are made to the approach of SOCs, they will never achieve their full potential, nor scale up and always be reliant on substantial public subsidies.

We set out here our own thoughts on how to break this logjam.

This third part of the paper sets out a new and revised approach to designing and delivering SOCs in the UK, drawing on our review of the evidence base as well as our own experience of assisting in SOC delivery. We are putting forward new ideas for how the Better Futures Fund could be designed to deliver more effective partnerships.

3.2 | Key design principles for a new approach

The core challenges for the current approach to SOCs can be summarised as follows:

These two issues have proved off-putting to potential public sector commissioners and also make the SOC approach a somewhat expensive cost to the public sector. It can also deter social investors from considering SOCs as a route for social impact.

Key design principles for a better approach must therefore include:

1) A simplified and more replicable approach to the three-way contracting between commissioner, delivery partner and social investor, preferably without the requirement to create an SPV

2) Simplified routes to investment for social investors

3)Transparency about the costs of contracting for external advisors

4)Transparency about the nature, amount and returns of social investment

3.3 | Proposing a new approach

We propose a new approach to SOCs for piloting. It would embody five key features, addressing the major weaknesses identified in the approach so far:

We set out these thoughts and proposals for discussion and further exploration. They are intended as a contribution to the ongoing national debate about SOCs and their place within public service delivery.

__________________________________________________________________

References

[1] Number taken from the Impact Bond Dataset, Government Outcomes Lab | Access here: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/indigo/impact-bond-dataset-v2/

[2] Hickman, E & Stanworth, N (2024) The value created by social outcomes contracts in the UK – updated analysis and report | Access: https://www.atqconsultants.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/VF-SOC-Social-value-report-update.pdf

[3] Data taken from: Anastasiu, A, Carter, E & Airoldi, M (2024) The Evolution of Social Outcomes Partnerships in the UK: Distilling fifteen years of experience from Peterborough to Kirklees, Government Outcomes Lab | Access: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/resource-library/peterborough-to-kirklees/

[4] Fraser, A., Tan, S., Boaz, A., & Mays, N. (2020). Backing what works? Social Impact Bonds and evidence-informed policy and practice, Public Money & Management, 40(3), 195–204 | Access: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1714303

[5] Stanworth, N (2019) A study into the challenges and benefits of commissioning Social Impact Bonds in the UK, and the potential for replication and scaling: Final Report, DCMS | Access: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60177d3b8fa8f53fbf42bde4/A_study_into_the_challenges_and_benefits_of_the_SIB_commissioning_process._Final_Report_V2.pdf

[6] A, Levitt et al (2023) Blog: How much does ‘it’ cost? Developing an understanding of transaction costs for impact bonds and social outcome contracts, Government Outcomes Lab | Access: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/community/blogs/how-much-does-it-cost-transaction-costs-impact-bonds/

[7] Outcomes Based Contracting, Web Article by: Government Outcomes Lab, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford | Access: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/the-basics/outcomes-based-contracting/#the-evidence

[8] For a highly sceptical view, see: Lowe, T (2023) Seven things to know about outcomes-based contracting, Blog article, Centre for Public Impact BCG | Access: https://centreforpublicimpact.org/resource-hub/seven-things-to-know-about-outcomes-based-contracting/

[9] Tomkinson, E (2016) Outcome-based contracting for human services, Evidence Base Issue 1, The Australia and New Zealand School of Government | Access: https://www.humanlearning.systems/uploads/Outcomes-Based%20Contracting%20for%20human%20services%20-%20Tomkinson.pdf

[10] P18, Big Issue Invest, Outcomes Investment Fund Impact Report 2022/23 | Access: https://wordpress.bigissue.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/OIF_report-v4.pdf

[11] Carter, E., Rosenbach, F., Domingos, F., & van Lier, F. A. (2024). Contracting ‘person-centred’ working by results: street-level managers and frontline experiences in an outcomes-based contract, Public Management Review, 1–19 | Access: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2024.2342398

[12] George, Thomas; Rogers, Jim; Roberts, Amanda (2020) Social Impact Bonds in the UK homeless sector: Perspectives of front-line link workers, Housing Care & Support, | Access: https://repository.lincoln.ac.uk/articles/journal_contribution/Social_impact_bonds_in_the_UK_homeless_sector_perspectives_of_front-line_link_workers/24387667

[13] Banes, S, Webster, R, Fox, C, Armitage, H. with additional input from Lepik, K-L (2025). Final Evaluation of the Skill Mill SIB, Policy Evaluation & Research Unit (PERU) | Access: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/resource-library/Final-Evaluation-of-the-Skill-Mill-SIB/

Sign up today and keep up to date with all our latest social impact news, innovations and insights so you never miss a thing.

Resonance Limited is a company registered in England and Wales no. 04418625

Resonance Impact Investment Limited, a subsidiary of Resonance Limited, is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Firm number 588462.

Disclaimer: This website does not contain, constitute, nor does it form part of, an offer to sell or purchase or a solicitation of an offer to sell or purchase, any securities, investments or financial instruments referred to herein or to enter into any other transaction described herein. Resonance is not providing, and will not provide, any investment advice or recommendation (personal or otherwise) to you in relation to any securities, investments or financial instruments or transactions described herein. Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this website, neither Resonance nor its officers accept any liability for its contents or for any errors or omissions.